Russia goads Britain with Antarctic oil fable

DEEP DIVE: British Conservatives want to drill for oil in the South Pole. They are playing into Russia’s hands

I was live on GB News last week to discuss widespread reports of a major oil ‘discovery’ in British Antarctica, made by a Russian research expedition in the Weddell Sea. Since the highly speculative find lies within a part of the South Pole claimed by UK, this ‘news’ pushed all the buttons of Britain’s ruling Conservative party — and their compliant friends in the increasingly alt-right-leaning UK media landscape.

Article stats: 2,300 words, 11-min reading time, 4 charts and maps

GB News, for the uninitiated, is the UK’s answer to Fox News: 24 hours of populist anti-liberal diatribes masquerading as news. One of its more popular shows is anchored by sitting Conservative MP Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg — the top hat-wearing Tory whose gentlemanly demeanour and debating acumen belie the privilege bestowed upon him by the British class system.

Rees-Mogg, who briefly served as energy minister during the short-lived administration of ex-PM Liz Truss, said Russia’s supposed ‘discovery’ of some 513 billion barrels of Antarctic oil is great news for Britain. He argued that more oil supply means lower energy prices, someone is going to get at it sooner or later, so let’s beat the Ruskies to it — international agreements be damned.

No mention of the ecological sensitivity of the Antarctic, the drilling moratorium enshrined in the 1959 Antarctic Treaty (to which the UK is a founding signatory), nor the simple fact that no major Western bank or investor would stomach the risks and reputational fallout from financing drilling in one of the last great untouched natural wildernesses on Earth.

I tried to set the record straight in the few minutes afforded to me, but it was an impossible task. Worse still, the talking heads who were wheeled out after me — including Kelvin Mackenzie, ex-editor of British tabloid newspaper The Sun — were given ample time to explain why Antarctic oil drilling must proceed at all costs.

Mackenzie spoke in a relaxed fashion about this triggering fresh conflict in and around the Falklands, sovereignty of which was of course the subject of a brief, bloody war in 1982. The UK’s victory in that conflict bolstered Britain’s geostrategic claim to its share of Antarctica — and, with hindsight, to the unquantified mineral treasures lying beneath its icy waters.

Russia has a long history of polar exploration dating back to the Soviet era. RosGeo, Russia’s state-owned exploration company, has undertaken numerous Antarctic surveys since 2011 under the guise of ‘scientific research’, which is permissible under the terms of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty. But RosGeo now openly states that it is assessing “the oil-and-gas bearing prospects of the Antarctic Shelf”, which marks a more confrontational approach.

RosGeo’s claim that there might be enough oil under the Weddell Sea to satisfy global demand for a decade or more seems to have triggered parts of the British establishment. Cue my invitation to appear on GB News to debate the dubious merits of ploughing ahead with resource extraction in this pristine natural environment.

More than meets the eye

I’ll be honest, I’m no Antarctic expert and the last-minute interview opportunity afforded little time to do much research. But the experience piqued my interest, so I’ve been looking at it more in the days since. The more I dug in, the more ridiculous the story appeared — and the more I sensed there could be more to it than meets the eye.

Any oil ‘find’ based on high-level geophysical seismic surveys is at best purely speculative and falls well short of any technical industry definition of a ‘discovery’ of proven or probable resources. In any case, geologists have known for decades about the likely presence of Antarctic oil deposits and — for a whole host of technical, commercial, environmental, political and moral reasons — left them undeveloped.

In purely economic terms, Antarctic oil would be among the most expensive molecules ever developed (remote location, harsh weather conditions, trillion-tonne icebergs drifting around) so for this reason alone would probably be the last barrels humanity ever develops (i.e. hopefully never).

The high cost base, uninsurable risks and long lead times would make Antarctic oil unattractive to purely financial investors: what certainty is there of recouping a big-ticket capital investment in the 2030s and 2040s based on prices that reflect that likelihood that oil demand has peaked?

Mischievous Moscow

Let’s get one thing straight: Russia is not about to mobilise capital, equipment and personnel at the other end of the world in the most inhospitable environment on Earth to dig up some of the most expensive and dangerous oil ever produced, when they have oodles of stranded resource in their own back yard. It’s a non-starter.

Russia is having enough trouble developing its own Arctic resources due to US sanctions that, as regular readers will recall, have severely hamstrung Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 megaproject in Siberia. President Vladimir Putin has even enlisted Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) to help navigate the obstacles that Western sanctions present to Arctic energy development.

So why even hint at interest in British Antarctic oil?

There are geostrategic benefits to making a play for this resource — or, more precisely, to be seen sniffing around this contested no-mans-land. It is the projection of intent that seems to be driving this story.

Russia-UK relations are rapidly deteriorating. Moscow says Britain is a de facto participant in the Ukraine war and recently expelled the UK’s defence attaché.

Bogged down in a victory-at-all-costs wartime mentality, the Kremlin is pursuing a strategy of confounding adversaries such as Britain in various theatres of operation. One string of this is to stoke discontent in sensitive areas of international diplomacy. An obvious place to start is to sour UK-Argentina relations, which are gradually improving after a meeting of foreign secretaries at a G20 summit in February.

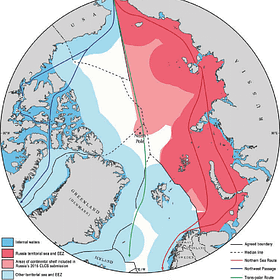

The Falkland Islands remain a bone of contention, as does the entire concept of ‘British Antarctica’. Britain’s South Polar territorial claims overlap substantially with those of both Argentina and Chile. The 1959 Antarctic Treaty froze all claims to sovereignty of the continent, so this situation remains unresolved. But all sides are taking a pragmatic approach to promote cordial relations.

Propagating ‘oil FOMO’ is a cynical and easy way for Russia to cause a ruckus. There are plenty of examples of oil discoveries exacerbating long-running territorial disputes, and not just in the history books. Just look at how Venezuela is escalating military activities in the Essequibo border region as neighbouring Guyana ramps up oil production.

Telegraphing the ‘discovery’ of gargantuan amounts of oil in disputed British Antarctica is a low-cost way of reviving tensions around both the Falklands and Antarctic sovereignty. If any side were to respond with provocative rhetoric around resource extraction, the ensuing diplomatic fallout could inflame not just relations between affected countries but perhaps all seven historic territorial claimants (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand Norway, the UK) — or even the 29 consultative parties with treaty voting rights.

These countries include Ukraine, China, and India, as well as the United States which, alongside Russia, “does not formally recognise the UK’s territorial claim and reserves the right to make its own claim in the future”. That’s according to Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at Royal Holloway University of London, who submitted written evidence to a UK parliamentary committee inquiry into Britain’s Antarctic interests.

The resource curse never goes away

The regulation of mineral mining activities has threatened Antarctic stability before. Treaty consensus broke down in the late 1980s over this very issue, precipitating a crisis that was resolved only with the 1991 signing of the Protocol on Environmental Protection (PEP) — which effectively banned mining. Notably, the UK was among those arguing against a permanent ban on mining, together with Japan and the US.

War in Ukraine is straining polar politics, both North and South. Just like in the Arctic, the conflict is fraying the Antarctic’s consensus-based system of governance and testing the resolve of Treaty signatories to protect the integrity of the no-mining protocol.

“There is widespread concern that a worsening relationship with Russia will spark strategic competition and make it ever more explicit in Antarctica,” Dodds wrote. International opposition to Russia’s February 2022 invasion is at best fragmented, and Moscow continues to work with polar protagonists such as South Africa, China and India.

The PEP is up for renewal in 2048, subject to a 75% supermajority of consultative parties voting in favour of any amendment. Twenty-four years is an eternity in politics but Russia and China always play the long game, and both are well aware that the 21st Century resource race will be very different to the previous hundred-year quest for oil dominance.

Precious metals and rare earth minerals are the new hydrocarbons, and Antarctica is believed to be home to large and valuable deposits. But the PEP moratorium prevented exploratory research, so current knowledge is limited.

The lack of exposed land and difficult field logistics also hinder prospecting. “Although the existence of mineral deposits in Antarctica is highly probable, the chances of finding them are quite small,” the US Geological Survey stated in 1974. But climate change and technological advances are challenging that conclusion.

Antarctica lost three trillion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2017, offering easier access to previously hidden swathes of territory. At the same time, “a new generation of robots and drones are peering under ice shelves, probing the ocean depths and monitoring glaciers,” Dodds wrote previously.

By 2048, global heating already baked in from accumulated atmospheric CO2 emissions inventory will have caused Antarctic ice sheets to recede even further. Climate change might drive colonisation by making the South Pole a less undesirable place to live. Future leaders may take the view that Antarctica is not such an exceptional place any more, and protecting its minerals bounty is constraining humanity’s ability to accelerate the energy transition.

21st Century resource wars

There are long-standing fears that an unregulated gold rush in Antarctica could lead to war. Speaking in the House of Commons in July 1989, junior Foreign Office minister Tim Eggar warned that without a multilateral accord “there is a real risk of a mining free-for-all, of heightened tension and possibly conflict, and of the collapse of the Antarctic treaty system which has served so well to keep Antarctica peaceful and stable for more than 30 years.”

While Eggar was referring primarily to hydrocarbons and conventional metal ores, he could have been speaking about a race to recover Antarctic energy transition minerals. With this in mind, Russia’s posturing around Weddell Sea oil deposits can be seen for what it is: an attempt to force a wedge issue into polar politics with an eye on a hotter, less stable future in which Antarctica’s real bounty might, one day, be up for grabs.

It is one thing for Putin’s Russia — in the midst of a revanchist military misadventure in Ukraine — to goad its adversaries with provocative claims to oil wealth in the Weddell Sea in pursuit of disruptive geopolitical aims. It is quite another for the UK — a cooperative player on the world stage that supposedly respects international treaties and conventions — to rise to this provocation and risk resuscitating historic grievances over its own ethically questionable military expansionism.

GB News frequently platforms some of the most unpalatable and ludicrous opinions. Promoting bellicose Antarctic oil drilling rhetoric is very much on-brand for the station. It’s easy to dismiss these views as fringe lunacy, but they have a nasty habit of normalising positions that the decent majority find abhorrent, and then becoming policy.

I’m under no illusion that a three-minute slot challenging Rees-Mogg’s half-baked oily jingoism will alter government thinking. But I couldn’t turn down the opportunity to present a more rational perspective.

Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 20 May 2024

🧠 Energised Minds

— Critical thinking on crucial energy issues —

“Power of Siberia 2 could prolong the LNG glut” — Russia’s expansion of pipeline gas exports to China would weaken China’s LNG appetite just as the market is struggling to absorb the ramp-up in new LNG export capacity, says the Center on Global Energy Policy

“Hydrogen should be limited to no-regret applications” — the misplaced hope that hydrogen can fix all energy problems is hindering progress to cut power sector emissions, the German Energy Independence Council tells Bloomberg

“The term ‘energy transition’ must be dropped” — the history of energies does not follow a logic of substitution and sometimes new sources can stimulate demand for old ones, argues historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

More from Energy Flux:

🧊 Drilling on thin ice 🛢️

War has shattered the Arctic region’s consensus-based system of governance, raising fears that long-simmering resource disputes could boil over. Will the energy crisis put Russia’s Arctic drilling programme on a war footing, or thwart Moscow’s ambitions?

REPOST: ❄️Frozen out of a warming Arctic🔥

It is hard to overstate the importance of the Arctic to Russia. Moscow lays claim to the lion’s share of the region’s immense energy and natural resources, and exploiting them is an overarching economic priority for Russia.

Russia’s stunted LNG coup

Russia has delivered the first drop of LNG from its heavily sanctioned flagship project, Arctic LNG-2. Moscow will hail the achievement as a victory over Western boycotts and proof that its domestic LNG industry is in rude health. In reality, however, the plant is likely to operate at severely reduced capacity and might never achieve its full potential.

Strong performance in the lion's den!