Greed over growth

DEEP DIVE: The relentless pursuit of profit is squeezing consumers and killing gas demand

Natural gas is, objectively, a highly valuable energy source. The fuel has distinct advantages, from dispatchable electricity generation to space heating to chemical feedstock. Gas-fired power is cleaner than coal at the point of combustion and is a flexible companion to renewables. But its biggest flaw is price. Why is gas so expensive? In a nutshell: complexity, commodification, financialisation, scarcity – and greed. These factors are undermining the growth prospects of gas in established and emerging markets.

Producing and storing natural gas is a complex process. Methane molecules must be discovered, surveyed, drilled, collected, piped, separated and treated, pumped along pipelines and held in specialised high-pressure tanks. If it’s going overseas, gas must be liquefied. This means super-cooling to minus 160 degrees Celsius, liquefaction at 200 times atmospheric pressure and loading the resultant LNG into cryogenic tanks aboard ocean-going vessels. At the receiving terminal it is warmed back into a gaseous state and pumped into the local gas network.

There is a financial and energy cost incurred at each stage. Between 10-15% of the original energy content is lost in liquefaction, transportation and regasification. The infrastructure to do so must be financed, built, insured and maintained. All of this must be paid for by consumers. The problem is, consumers are consistently paying prices well above the cost of production and delivery.

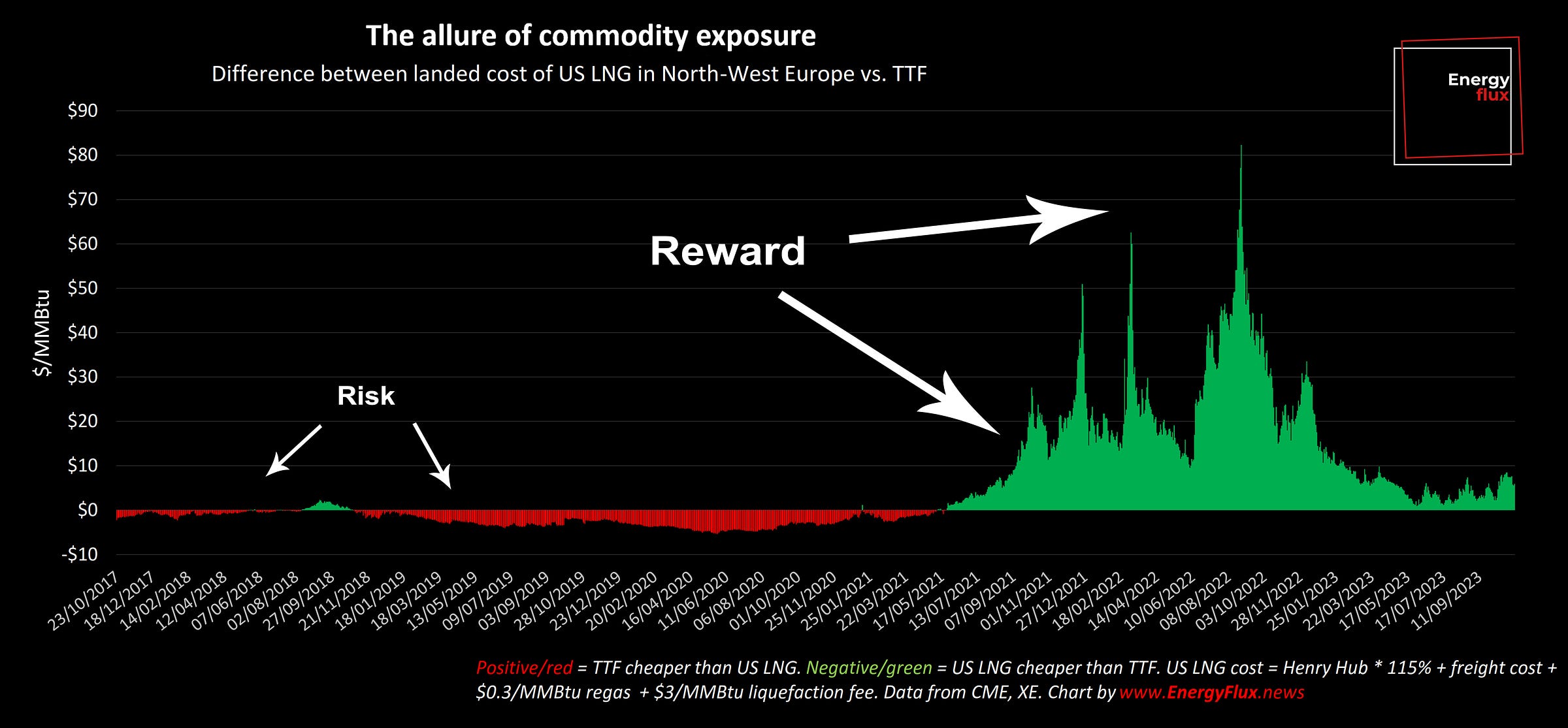

There are huge margins to be made on LNG shipments to Europe. The cost of producing American LNG and hauling it across the Atlantic tends to be above the cost of gas delivered by pipeline. But it rarely dips below the traded price of gas on the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF), Europe’s gas benchmark. Why is this?

It was not always thus. Pre-Ukraine, the landed cost of US LNG was frequently above TTF but plant shut-ins were rare due to commercial structures. Offtakers signed take-or-pay agreements to lift cargoes or pay a penalty. The cost of liquefaction – which is typically around $3/MMBtu – is deemed a sunk cost so is discounted from the calculation of whether to lift cargoes.

Only when the loss on lifting a cargo rises above the cancellation penalty does it make sense to cancel a scheduled US LNG cargo. This last happened in 2020, when Covid-induced lockdowns artificially suppressed demand and dragged gas hub prices into the doldrums.

Since mid-2021, when Russia began outwardly weaponising pipeline gas deliveries to Europe, TTF has been on a dizzying journey of volatility that has made US LNG look cheap by comparison. The whipsaw to the upside has been spectacular, and everyone involved in the gas value chain wants a piece of the action.

Hustling for value

Rather than being on the receiving end of this trade, utilities have sought to claw back value by venturing closer to the source of production and taking on volume risk. They’ve done this by signing US LNG sales and purchase agreements (SPAs) with the take-or-pay (TOP) clauses mentioned above.

At the other end of the chain, LNG margins also caught the attention of American gas producers. Rather than handing over their molecules at the going rate on Henry Hub, shale gas companies want exposure to European market pricing. Shale drillers such as EOG Resources, Tourmaline Oil and Apache Corporation were first movers, signing deals to supply feed gas to LNG plants at prices indexed to international benchmarks.

Chesapeake Corporation last week took it a step further, signing a Heads of Agreement with trader Vitol to supply LNG at a price indexed to JKM, the Asian spot LNG benchmark. The deal is interesting because Chesapeake is not an LNG producer; the agreement requires both parties to find a plant they can use to liquefy the gas. Agreeing the terms of an LNG contract without involving the LNG producer relegates the liquefaction plant to a service provider charging a fixed fee per unit.

This is how the US LNG industry used to operate. The first wave of US liquefaction plants provided liquefaction as a service for which they tolled a fixed fee to third parties. Cheniere Energy broke the mould by venturing into the upstream to purchase its own feed gas, liquefy it and sell it ‘free on board’ under binding SPAs with TOP clauses.

But control over the upstream resource was not enough. LNG producers could see the upside being captured by their customers, and wanted in. Cheniere achieved this by reserving some of its LNG output to sell on a merchant basis to traders, utilities and industrials in LNG-importing countries.

Chesapeake’s move to push the LNG plant out of the commodity play thus brings the model full circle. It is the latest powerplay in the endless hustle for a piece of the margin pie. Every market participant is constantly haggling over the terms of exposure to maximise their upside while minimising risk of becoming the bag-holder when markets go south. This relentless pursuit of extracting the highest profit from every stage of the LNG production process drives up costs for consumers.

The curse of financialisation

But that doesn’t fully account for the exorbitant premiums being paid today by European consumers. This is where commodification and liberalisation come into play.

Liberalisation removed barriers to market exchange, allowing buyers and sellers to transact with greater ease and transparency using standardised contracts for gas delivery. Liquidity was fostered by neoliberal European regulators fixated on free market ‘price discovery’. They designed markets that encouraged speculation on future gas prices using financial instruments. Financialisation attracted more market participants including investors and speculators – market participants highly attuned to signals of supply and demand fluctuation.

Financialisation brings the future into the present. The likely impact of unfolding events on the future gas supply balance is factored into prices payable today, which influences trading psychology, behaviour and real-world outcomes. Humans are by nature emotionally sensitive to news of war and geopolitical events. Liberalisation and financialisation have transposed that sensitivity into gas price formation.

In the most deep and liquid gas markets such as TTF, trades are today settled on the basis of sentiment and the primary commodities are capital and information, not physical molecules of gas. As technicals overtake fundamentals, inherent value and cost of production become almost an afterthought.

Large financial players such as US hedge funds and Asian investment funds are today the market makers, accounting for an estimated 30% of gross TTF positions. These entities have the capital and heft to move prices 10% or 20% in a week, or even within-day, as occurred during last week’s correction.

Markets are accelerating

Susceptibility to sentiment is accelerated by exponential advancements in technology. In this realm, speed of execution is everything.

Algorithms analyse vast amounts of market data and execute trades based on predefined rules, optimising entry and exit points and reacting swiftly to market changes. Artificial intelligence gives traders an edge, responding in real time to regulatory announcements, weather forecasts, breaking news events and even market rumours.

Predictive analytics anticipate natural gas price movements and are particularly valuable in getting ahead of short-term fluctuations. Machine learning can identify patterns in market data to help traders adapt their strategies to changing market conditions and inflate their risk-adjusted returns.

Automation has had a startling impact on TTF traded volumes. Intercontinental Exchange celebrated a record 5.7 million TTF futures and options traded during May 2023, equivalent to 4,158 terawatt-hours (TWh). That’s more than the EU’s entire annual gas consumption in 2022. If these traded volumes are sustained over the full year, the implication is that each unit of gas consumed in the EU will have changed hands on average between 10 and 15 times before reaching consumers.

A lot of this activity reflects prudent risk management by utilities, producers and other physical players with exposure to the underlying commodity. These market participants benefit from the liquidity that financial players bring. Heightened volatility is often observed when liquidity is low and covering an out-of-money position – a so-called ‘stop loss’ – becomes expensive.

But the increasing presence of financial players placing large bets on TTF also stokes volatility and inflates prices. Short sellers must cover their positions when prices rise by buying back paper volumes, which accelerates the bull run. Physical buyers are forced to swallow these prices on the way up, and they must also keep buying on the way down – moderating bearish corrections.

Who wants more gas?

In a European market still recalibrating to the loss of Russian gas, the net effect of this market structure is to magnify movements in both directions while also keeping prices elevated. Europe has enough gas in storage to weather even the harshest of winters, and forecasts are for a mild, wet and windy El Niño northern hemisphere winter. TTF fell 10% last week and yet it is still trading at a ~63% premium to the landed cost of US LNG.

Europe’s reliance on LNG for energy security means TTF now increasingly drives global gas pricing. This is kryptonite for LNG demand growth in emerging markets. Coal-dependent South-East Asian economies are highly unlikely to switch to an expensive and volatile fuel that places them at the whim of haywire and unpredictable European market sentiment.

For countries with established gas markets and a declining domestic supply base, LNG can provide a convenient backfill solution while downstream consumers adjust and new ways are found to power their economies. But wherever coal is king, the heir apparent is not gas. Renewables are tracking up the S-curve of adoption, and the current inflationary readjustment in wind and solar will at most merely temper that trend. It will not prompt a course correction.

Integrated energy majors such as Shell, BP and TotalEnergies are staking their collective future on double-digit energy demand growth in emerging and developing economies. Their thesis is that lifting people out of poverty requires energy, and cleaner air. This much is true. But the idea that ‘cleaner burning’ gas is the solution is mistaken. Price is everything, and wildly expensive energy sources will lose out every time.

Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 6th November 2023

More from Energy Flux:

Energy transition = volatility (part 2)

The EU pioneered energy market liberalisation in the belief that free market competition delivers efficiencies that drive down the cost to consumers. The experiment with market-based pricing for natural gas paid off: EU retailers and heavy industry saved billions of euros on gas import bills over the past decade – but will these savings endure? As the winter energy crunch morphs into a full-blown energy crisis, the pitfalls of liberalised energy trading are coming to the fore.

The 27 Club

“Where are the feasts we were promised? Where is the wine, the new wine, dying on the vine.” – Jim Morrison How much gas will the world need in 27 years’ time? This question matters not just because it takes us to the feted mid-century point by which many countries have pledged to achieve ‘net zero’ emissions. For Shell and TotalEnergies, the answer will determine whether their latest bold bets on liquefied natural gas pay off.

Gas bubble?

European natural gas prices have retreated from recent peaks but remain unsustainably high. The initial shock of events in Israel and the Baltic Sea is giving way to a creeping realisation that gas fundamentals remain weak. European LNG imports have fallen by a third since the summer even as prices rose by the same proportion, suggesting a correction is due. But LNG traders can still make a killing before that happens.

This is a great explainer for those who are new to energy markets, but a bit old hat to more veteran observers/participants. You've got great stuff here, and you explain well. Maybe you could delve more into prognostication, and maybe talk about the factors that could drive the different future scenarios?

There is a vampirism about the market in energy generally and they’re partying hard. Seems like they are desperately trying to put off the rising of the sun by turning up the music. We can dance along or we can leave the party.