The TTF transparency gap

FREE POST: Inadequate data and lax regulation obfuscate what’s really driving EU gas prices

The niche topic of speculation in European natural gas markets is attracting media interest, triggering a debate around the influence of hedge funds on energy prices. This is to be welcomed. However, there is no way of reconciling conflicting views without more robust data and better regulation. This post sets out what we know, what we don’t, and what should be done about it.

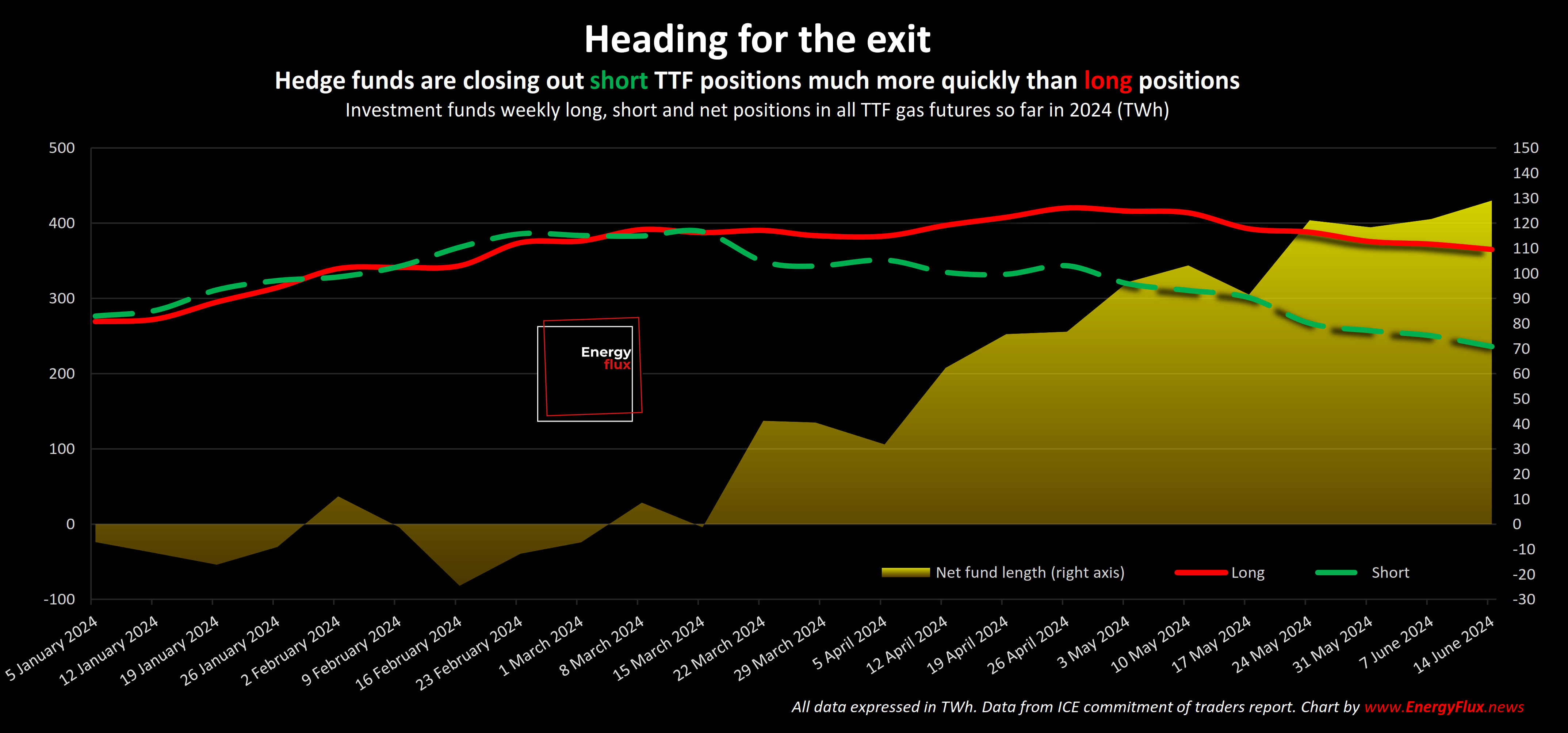

- If you’re new to Energy Flux, here’s a quick catch-up: anyone who trades futures contracts on Dutch TTF, the main EU natural gas trading hub, must disclose their long and short holdings every week. Hedge funds have increased their net length in TTF in recent weeks, and regression analysis shows that this is having at least some impact on prices. More on this here, here and here.

Investment funds increased their net long position in Dutch TTF futures to 129 terawatt-hours (TWh) in the week ending 14th June 2024. This was covered by two major price reporting agencies: Argus Media and ICIS.

The mere suggestion that speculative capital might be influencing prices generated some pushback. There’s a lot to say about this, but first let’s clarify a few matters relating to the data itself.

Data discrepancies

Depending on the source you’re using, 129 TWh is either a two-year high or an all-time high for investment fund net holdings in TTF futures. Confusingly, there is more than one version of historic data from the Commitment of Traders (CoT) report, and analysts are now poring over the numbers to ascertain which is the most accurate.

I don’t want to prejudge those findings but am keeping a close eye on this, because the discrepancy is considerable and it matters in terms of how we should think about what’s going on in the market today.

One version seen by Energy Flux shows that speculative capital held a whopping 262 TWh of net TTF length on 16th April 2021, just as the epic post-Covid, pre-Ukraine EU gas bull run was gathering steam.

That’s a phenomenal amount of gas, equivalent to roughly 27 billion cubic metres — more than the annual gas consumption of the Netherlands in 2023. If correct, this data tells us that there is a precedent for hedge funds to make even more wayward bets on EU gas futures than they are currently.

That same dataset shows investment fund net length peaked again at 133 TWh on 21st January 2022, which is also more than the 129 TWh they currently hold. And we all know how 2022 panned out in European energy markets.

So, point number one: we need better data to put today’s speculative capital flows in the right context. Are hedge funds placing all-time record bets on rising EU gas prices, or are they merely warming up?

(For the record, the MiFID II CoT data is published by ESMA, the European Securities and Markets Authority, here. This dataset goes back to 2018. An alternative dataset is published by ICE every Wednesday here, but it only goes back a few weeks, and EEX has its own CoT data here. Refinitiv/LSEG and Bloomberg also offer their own versions but these are not publicly available, and there are discrepancies between all of them. ESMA looks like this most reliable version.)1

Dissecting the rebuttal

With journalists asking all the right questions about hedge funds’ multi-billion-euro gas bets, a rebuttal was inevitable. The most provocative to date came from Energy Aspects, a global research firm that counts oil majors, producers, traders, governments and investors among its client base.

Energy Aspects took to social media to offer a “non-sensationalist” view of investment fund flows in TTF futures. The company highlighted that recent increases in net fund positions have “actually been driven by the closing of short positions, not an increase in new bullish positions”.

This is true: hedge fund long positions peaked at 420 TWh on 26th April 2024 and have fallen every week since then, with the latest data showing a total of 365 TWh (15%).

Short positions have been unwound much more quickly, falling from 343 TWh to 235 TWh currently (-32%). This has driven up their overall net position from 77 TWh to 129 TWh over the same timeframe (+68%).

Total market exposure — short plus long positions — has fallen from 763 TWh to 601 TWh over the same period (-21%). So, you could say hedge funds are retreating somewhat from EU gas futures, but an asymmetry in the winding down has left an increasingly large residual net length.

Moreover, hedge funds still hold record volumes of TTF futures on their books. Both sets of CoT data show that, prior to February 2024, investment funds had never had more than 700 TWh of total exposure to TTF.

They might have reined in their exposure somewhat since March, but we’re still in unprecedented territory in terms of how much speculative capital is sloshing around in this market.

Energy Aspects made other claims that are hard to fact check. For example, the CoT data apparently “contain delta-adjusted option positions” which “likely inflates the net number”. I am yet to see a version of CoT data that explicitly breaks out TTF options, so this point is moot (please let me know if I have missed something).

The firm also “estimates” that “funds actually took large bearish bets on summer 2024 TTF prices while offsetting these positions with long positions in winter 2024 contracts”, i.e. they are playing the seasonal calendar spread.

Again, no way to easily verify this without inside knowledge of what hedge funds are actually buying, because the EU regulations do not require this level of disclosure (more on this below).

Their final claim — that investment funds “are not puppet masters” and they do not “attempt[…] to control the market” — seems to be a direct reference to the image I used to illustrate my first article about this, Funds versus fundamentals.

This rebuttal is simply an opinion. Hedge funds are notoriously tight-lipped and rarely, if ever, speak publicly about their trading strategies or motivations.

So, yes, they might be honest brokers looking to take billions of euros of client’s money for a fun ride on the TTF rollercoaster and see what happens. Or maybe not. Who can be sure?

Shining a light

That brings me onto the next point: we need better regulation to improve transparency.

The EU’s ’s markets in financial instruments (MiFID II) regulation, which requires market participants to disclose their weekly long and short TTF positions, is a blunt instrument. To recap from this post, it groups together all the pools of capital into three broad groups:

- Investment Funds (i.e. hedge funds/speculative capital)

- Commercial Undertakings (physical players, e.g. gas producers and utilities)

- Credit Institutions (any counterparty, i.e. investment bankers, brokerages and traditional banks).

These groupings obscure the nuances in the types of capital and their risk appetite. A larger number of categories with more precise definitions according to fund size, institution type and business activity would tell us more about who is holding TTF futures and what their motivation might be.

This is particularly pertinent because (and you will excuse the hearsay) I am told that many investment funds disclosing TTF positions also own interests in critical infrastructure such as pipelines and gas production facilities.

There is no way to verify this, but better regulation requiring TTF market participants to disclose all relevant business dealings would help us understand why certain funds behave the way they do.

It might even expose or prevent manipulation. There’s a theory doing the rounds that investment funds might have teamed up with physical gas producers and suppliers to back up their paper positions and move the market in their favour.

The theory is unsubstantiated, but this is how it might work: both sides buy long before a deliberately engineered ‘unscheduled outage’, then prices rise: hedge funds make a killing and cash out, and the producers save some molecules to sell at a higher price after the event. Everyone’s a winner.

That’s according to Endre Moldvay, an outspoken quantitative engineer and ex-energy trader who posts epic threads about TTF speculation under the X handle of ‘Illusionist’. To be clear: this is pure speculation, but the fact that we can’t rule it out speak to the opacity of the market and paucity of disclosure requirements.

More granularity, please

The MiFID II regulation should also make market players disclose (anonymously) the actual contracts that they hold.

When CoT is updated, all we know is that these groups increased or decreased their long and short holdings in a generic basket of TTF futures. There is no requirement to break this down into monthly, seasonal or yearly TTF futures.

If we knew that, say, 30% of hedge funds’ current 129 TWh of net length expires in October 2024 then analysts could make reasonable assumptions about whether and when these positions might be unwound. This would help ‘genuine’ market participants to hedge their exposure to this inherently volatile commodity.

End-users are struggling to second-guess a market that is, frankly, saturated by speculative capital at volumes capable of moving the entire forward curve by double-digit percentages on any given day of the week.

Lower position limits

There is a limit to how much paper gas a hedge fund can hold at any given moment. This volume is decided by Dutch financial markets regulator AFM, with EU oversight from ESMA, the European Securities and Markets Authority.

The position limits were lowered in 2022 but are, arguably, still way too high. The spot month position limit is 17 TWh and other months (i.e. contracts with expiry further out on the futures curve) is 101 TWh.

Given that there are more than 300 hedge funds trading TTF futures, these limits allow speculative capital to hold more than 30,000 TWh of gas futures. That’s more than six times the annual consumption of the entire region of Europe (including the UK, Norway, Turkey and Ukraine).

To put it another way, a single hedge fund could in theory hold gas futures equivalent to almost three times the annual consumption of Norway and still be compliant.

Under MiFID II, limits must “prevent market distorting positions”. It is hard to argue that the current limits achieve that. Maybe as well as a hard volumetric cap, there need to be a dynamic cap defined as a percentage of all traded TTF volumes?

So, to conclude, our understanding of the influence of speculative capital on TTF prices is limited by a lack of transparency. Nature abhors a vacuum, so it is only natural that speculation about the speculation (meta-speculation?) fills the void of information.

These four measures would improve matters:

- A single authoritative and publicly available historical CoT dataset

- More precise definitions of each market participant, including related business disclosure

- A requirement to disclose the expiry dates of all traded TTF volumes

- Lower position limits, and/or a dynamic cap

To be clear, I’m not an expert on any of this and I welcome alternative views. I have no skin in the game and my sole motivation in writing this is to foster informed debate, because gas prices impact lives and livelihoods. Please feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments section, or send me an email in private.

Seb Kennedy | Energy Flux | 24 June 2024

Good, honest research takes time. If you value independent market analysis, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber — and keep Energy Flux going

More from Energy Flux:

This paragraph was updated on 27/06/2024 to add a link to the ESMA and EEX data, to clarify the discussion around various data sources and to explain that ESMA data is probably the most reliable. ↩