The Asian LNG glut is here

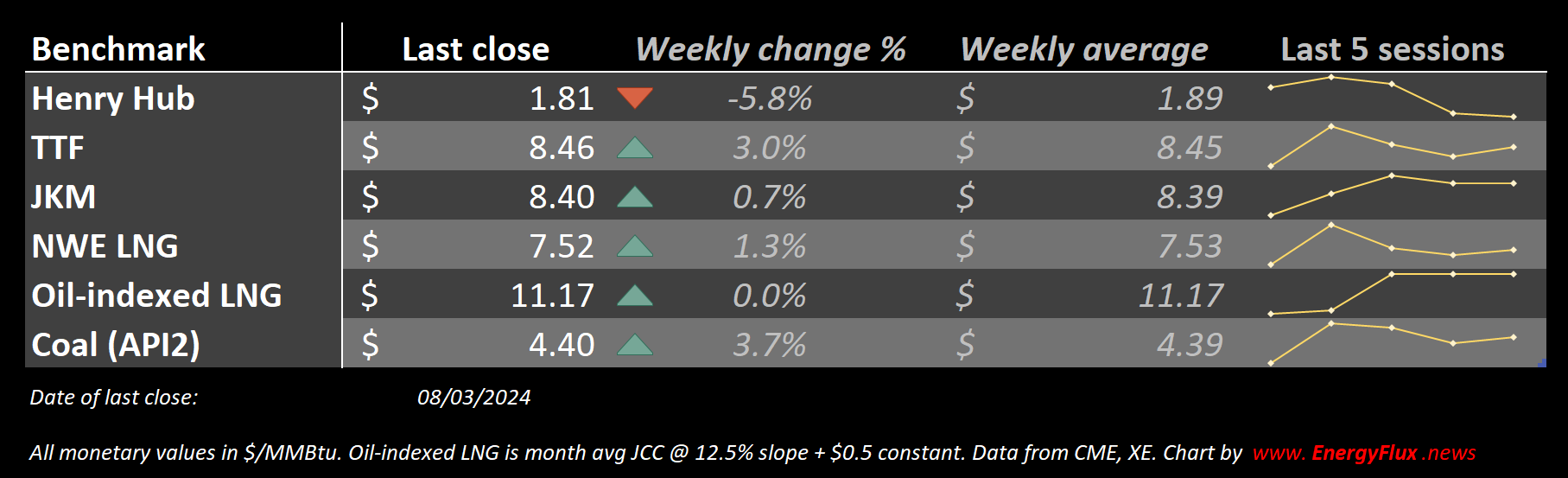

Widening gulf between LNG spot prices and oil-indexed contracts is squeezing sellers | EU LNG Chart Deck: 4-8 Mar 2024

The first indications of oversupply are manifesting in the Asian market for liquefied natural gas (LNG), triggering a shift in market power from sellers to buyers.

Asian buyers are flexing down the volume of LNG they lift under long-term oil-indexed contracts in order to scoop up much cheaper cargoes in the spot market.

This is happening because weak demand is keeping the spot price significantly below LNG contracts that are pegged to the price of crude oil.

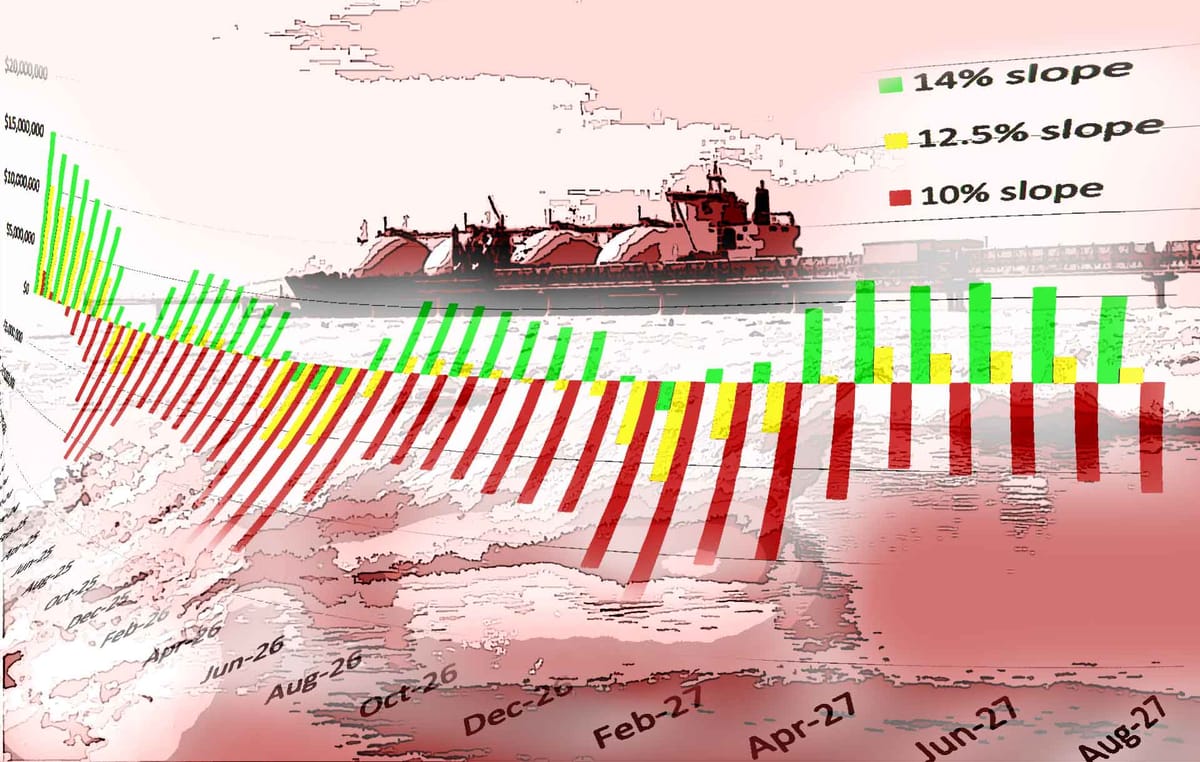

Analysis by Energy Flux shows that Asian LNG buyers could save as much as $15 million for every oil-indexed cargo they replace like-for-like in the spot market. The savings come at the expense of sellers.

The precise saving depends on the ‘oil slope’ — the formula used to calculate the price of LNG under the contract. This is a percentage of the relevant crude oil price, usually either Brent or Japan Crude Cocktail (JCC).

This post analyses the oil-LNG price dynamic, and considers what a spot discount could mean for the balance of global LNG trade over the coming months — and the implications for European energy markets.

🧠 I’ve also reintroduced Energised Minds — a section at the end of the newsletter where I highlight a few interesting energy essays, charts and reports on my radar.

Article stats: 2,000 words, 10-min reading time, 9 original charts & graphs