Madness at the margins

DEEP DIVE: For better or worse, marginal pricing of electricity is here to stay

Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, severing the link between gas and power prices was a core UK policy objective. The 2022 crisis focussed minds, but government ruled out alternatives to marginal pricing. Now, rampant speculation is injecting fresh volatility into European gas trading hubs. Is the British electricity market condemned to a future of endless gas-induced price spikes?

Overview:

- Amid intense debate over locational power pricing in the GB market, the rationale for linking electricity prices to the most expensive marginal generation unit has gone largely unscrutinised

- Marginal pricing is becoming problematic with the rise of renewables, as the opex-based pricing regime fails to remunerate for wind and solar power capex without marginal gas generation

- Hedge funds speculation is driving volatility in European gas markets, which is being passed through to power prices via marginal pricing

- A lack of credible alternatives to marginal pricing points to an increasingly volatile transition towards full grid decarbonisation

Article stats: 2,800 words, 13-min reading time, 6 charts and graphs

Marginalised in the debate

The UK government’s ongoing Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) threw the doors open to locational marginal pricing (LMP). This is a potential move away from ‘nationwide’ power pricing, and towards a mosaic of prices for each geographically determined ‘zone’ in the GB market.

The lively debate around LMP focused on the ‘locational’ aspect. A decision on whether to proceed with zonal LMP is hotly anticipated by all stakeholders. The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) is still entertaining the idea.

The ‘marginal’ aspect of LMP received much less scrutiny. DESNZ considered alternatives but threw them out in the second phase of REMA, in May 2024. Marginal pricing was, well, marginalised in the REMA debate.

With all the angst and vested interests lobbying hard both for and against locational pricing (and other aspects of REMA), the incoming Labour government inherited a bulging to-do list from officials at DESNZ. Revisiting marginal pricing is definitely not on the agenda.

Power pricing orthodoxy

The reliance on the ‘marginal’ generator to set prices for all power producers is a central tenet of wholesale power price formation the world over. But it is, arguably, the root problem. Many of the complex sticking-plaster policy interventions in power markets are actually trying to solve for this.

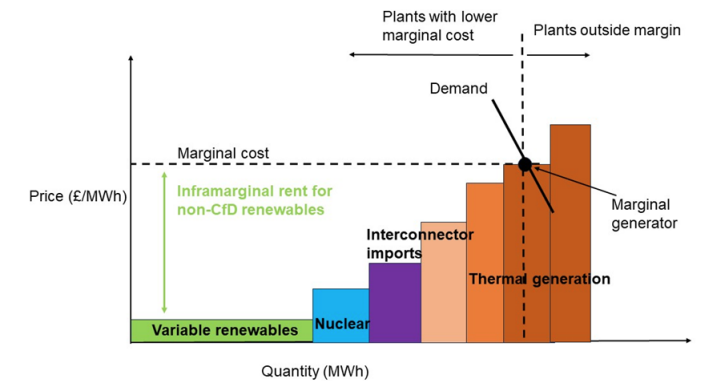

In a marginal pricing system, the most expensive plant, which is required to meet the last unmet unit of demand at the margin, sets the price for the rest of the market.

In electricity, that’s usually thermal generators with fuel costs. Traditionally this was coal, but latterly gas-fired power has taken the mantle of price-setter. All generators with costs below gas – e.g. wind, solar, hydro and nuclear – therefore receive ‘infra-marginal rent’: the difference between their short-run marginal cost (SRMC) and the cost of gas-fired generation.

Marginal pricing is widely used in commodity markets, including liberalised electricity markets. It works well when producers have similar operational performance profiles and technical product characteristics. The lowest cost assets/producers are rewarded the most, encouraging greater efficiency.

Irreconcilable differences

Integrating wind and solar into the generation stack was always going to run into a structural problem: these sources have very different properties to incumbent sources. Chiefly, renewables have large up-front capital costs (capex), no fuel costs and very low operating costs (opex).

In a hypothetical sense, and in the absence of subsidies, renewables need gas. Infra-marginal rents (generated by price-setting gas) cover the long-run capex costs of renewables. If the marginal generator had very low opex (e.g. nuclear) then wholesale prices would be too low to remunerate renewables adequately.

Therefore, to keep renewables investors whole, prices would have to clear up to a level that reflects the long-run cost of capital. In reality that does not happen, which is why European power markets are witnessing more frequent and prolonged periods of low/negative pricing, as has documented over at (link).

Renewables and gas differ in other key ways. Renewables output varies depending on weather and location, while gas is dispatchable, flexible and location-agnostic. In a pricing regime based on the marginal producer, these fundamental differences cannot be reconciled in an economically logical way.

The tide is going out

Full decarbonisation of electricity implies transitioning from an opex-based pricing regime to a capex-based one. The end destination might be a glorious utopia of clean, cheap, stable power supplies, but the journey will be tortuous. Friction is unavoidable, but so far it has been manageable.

Prior to 2021, the reliance on marginal power pricing was not overly problematic. This was thanks to the combination of relatively benign gas market conditions and the low penetration of zero marginal cost power sources. Gas was cheap and renewables were only a small disruptive force.

Today’s post-Covid, post-Ukraine world is quite different. Rampant speculation is fuelling gas price volatility. An onslaught of cheap solar is flooding grids for hours on end before abruptly tailing off. In this world, pricing electricity off the marginal electron loses any sense it might once have had.

Excess speculation

Marginal pricing might not be getting the scrutiny it deserves in the UK. But there is a growing awareness in Europe that excessive speculation by financial traders is fuelling gas price volatility – and that, thanks to marginal pricing, this volatility is being passed through directly to power markets.

The European Commission recently published a landmark report by Mario Draghi on the future of European competitiveness.

The former European Central Bank (ECB) president called for better regulation to “limit the possibility of speculative behaviour” in EU gas markets. These drive prices both in EU-adjacent markets such as the UK and in gas-importing regions around the world.

Draghi’s intervention is timely. Hedge funds and other financial investors are taking increasingly wayward bets on the future direction of prices on Europe’s benchmark gas trading hub, the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF).

Speculation feeds volatility

Investment funds have rapidly increased their exposure to EU gas prices since late 2021. At this point, the market tightened suddenly amid Russia’s deliberate disruption to pipeline gas flows ahead of its land invasion of Ukraine.

War and extreme scarcity pricing in 2022 gouged consumers and offered an extraordinary money-making opportunity for ‘non-physical’ traders in European gas futures. Those are financial players who deal exclusively in derivatives and do not handle the underlying commodity.

The Dutch TTF trading hub fosters speculative trading by allowing non-physical funds to build very large long (or short) positions and ‘roll over’ their exposure from one month to the next. This means they never have to take physical delivery of the underlying commodity.

Speculative capital has poured into bullish bets on TTF, amassing net long positions worth an estimated €8-9 billion (£6.7-7.6bn) in aggregate. US and Asian hedge funds are believed to be major holders of speculative positions, which flipped extremely bullish in recent months.

The movement of funds is exerting ever-greater influence over price formation on TTF, Europe’s most liquid gas trading hub. The liquidation of short positions, combined with the opening of new long positions, fuelled a bull run in gas prices over the summer.

The front-month contract on TTF soared 75% between February and August, from lows of ~€23 (£19) per megawatt-hour (MWh) to peak at €40 (£33.7) per MWh at the end of the summer. The price surge correlated with investment funds shifting from a net short TTF position of -22.5 TWh in February to a net long position of 268 TWh in August, according to data from the European Securities and Markets Authority.

No obvious solution

In his report, Draghi suggested the EU should introduce more stringent financial position limits and dynamic caps. He also said there should be an “obligation to trade in the EU” to counteract these types of speculative excesses.

He called for better regulatory oversight of energy and energy derivatives markets to “anticipate unusual trading patterns and allow for quicker and more efficient remedial action”.

Draghi also addressed the question of marginal pricing, although he stopped short of calling for an alternative price-setting arrangement.

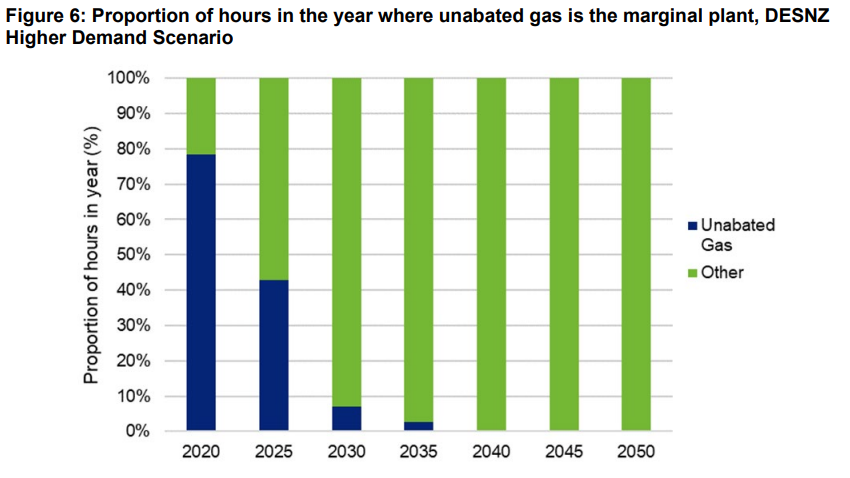

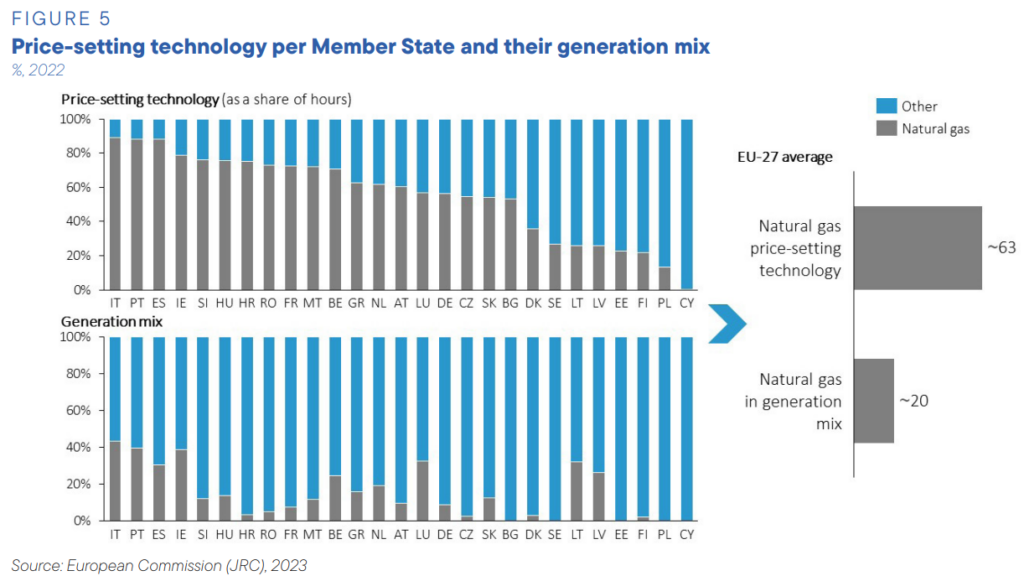

“In 2022 at the peak of the energy crisis, natural gas was the price setter 63% of the time, despite making up only 20% share of the EU’s electricity mix,” he wrote, adding:

“In the absence of action, this decoupling problem will remain acute at least for the remainder of this decade. Even if renewable installation targets are met, it is not forecast to significantly reduce the share of hours during which fossil fuels set energy prices by 2030.”

Rather than exploring alternative methods of price-setting, Draghi suggested the use of long-term contract solutions such as Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) or Contracts for Difference (CfDs). These, he said, would “help attenuate the link between the marginal price setter and the cost of energy for end users”.

These are exactly the sticking-plaster solutions that the UK has also opted to advance, while persisting with marginal pricing at the core of the GB electricity system.

Missed opportunity

REMA is the biggest upheaval of the GB power market since the start of liberalisation and privatisation in the 1980s. One might have thought this would present an opportunity to grapple seriously with the fundamental question of whether marginal pricing is an appropriate basis for a capex-based generation stack.

Instead, the chosen policy response is to add more sticking plasters.

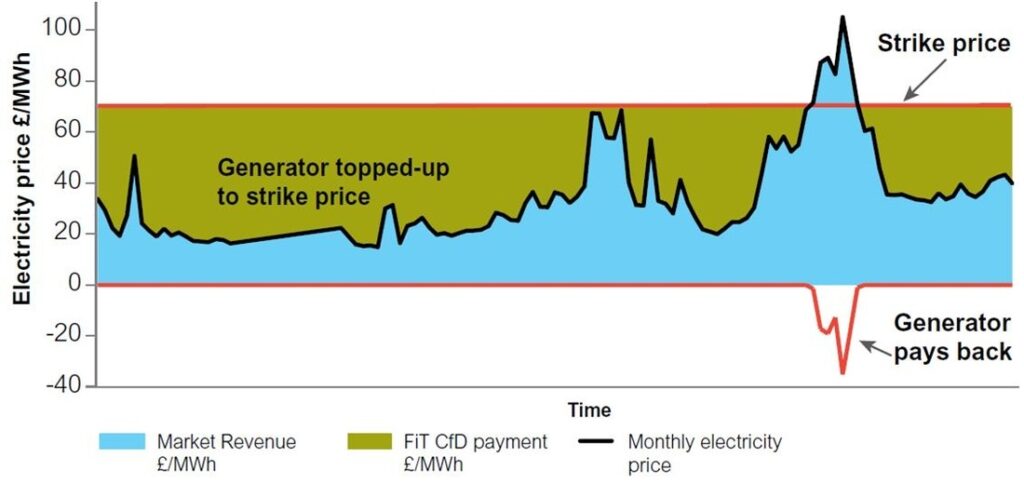

Do not be mistaken: PPAs and CfDs are highly effective instruments that can and will continue to underpin phenomenal amounts of investment in critical energy transition infrastructure.

The CfD, in particular, mitigated the worst extremes of the 2022 energy crisis. It forced generators to pay back excess remuneration when wholesale prices (set by gas) soared far above their agreed strike prices.

But at the other end of the spectrum, the combination of marginal pricing and CfDs has precipitated a knotty problem of increasingly frequent zero or negative pricing periods, price cannibalisation and escalating subsidy support costs for top-up payments.

Negative energy

If the GB market persists with marginal pricing, as is the plan, then the only way to avoid passing gas price volatility through to power consumers is to push gas off the system. It can only achieve this by rapidly accelerating deployment of wind, solar, nuclear, energy storage. More progress is also needed in demand response technologies to render gas entirely unnecessary, save for a few crucial hours per year.

But installation rates of wind and particularly solar might hit the skids without swift regulatory intervention. Solar generation is highly correlated, with midday peak generation and nothing at night. As such, it is plunging wholesale prices into zero or negative territory with alarming frequency.

“Regulators, rightly, will not want to encourage more solar production at times when production is already plentiful (and now even excessive, at times),” says Jérôme Guillet, managing director of energy transition finance company SNOW.

This means new solar producers must no longer receive a positive price for their electricity when there is already too much of it. This is precisely when they will all be producing.

“The scale of the problem may even require action against existing producers, which is much more problematic as they based their investment decisions (and continuing financial obligations) on the past revenue regime,” Guillet wrote in his Substack, .

Competing objectives

One potential solution is to switch to an entirely new renewables subsidy regime based on capacity rather than generation.

Under the CfD, the generator sells their power in the wholesale market. The CfD pays generators the difference between the wholesale power price and an agreed strike price, beyond which they must pay back the difference.

DESNZ is consulting on the ‘deemed’ CfD as part of the second phase of REMA. Under this mechanism, renewables generators would be remunerated based on their deemed output – not their actual production.

The process of ‘deeming’ output means estimating production 24/7 and paying subsidies out as if the asset had been generating. This protects the wind or solar investor from negative pricing periods. It allows the asset to be curtailed without having to pay it to shut down.

Ostensibly this is solving for grid congestion-related curtailment, which is another ballooning problem of grid decarbonisation. But, as a capacity-based payment approach, it represents a shift from an opex to capex-based pricing regime. As such, it is very much compatible with the needs of financiers.

Sadly, protecting the asset from price signals introduces operational challenges related to efficiency of plant design and dispatch.

Capacity-based CfDs “would definitely make projects financeable, and would help grids manage the occasional surpluses from solar,” Guillet wrote, adding:

“But it would certainly not incentivize developers to optimise either the location or the performance of their projects, and it would not help the development of batteries and other demand-management initiative to the same extent that current price swings will.”

Better the devil you know

There is no easy or quick solution to the problem of real-time price-setting of electricity from a highly diverse mix of generation sources.

The considered opinion of DESNZ and many others is that marginal pricing is ‘better the devil you know’. It is easier to futureproof the CfD sticking plaster than tear it off and try an entirely new, untested remedy. There are precious few real-world examples of capex-based wholesale electricity pricing that are relevant to the UK context.

Brazil operates on a cost-based dispatch model, which helps reduce price volatility. This is important in managing Brazil’s hydroelectric-dominated power system. However, the lack of market-based price signals for scarcity or abundance limits incentives for the efficient deployment of new flexible resources like energy storage or demand response – which will be vital to the UK energy transition.

What all this means, in all likelihood, is a very bumpy and volatile transitional period for the GB power system. The shift away from a handful of price-setting thermal generators is well underway. But we are a long way from the new dynamic system of clean power supplied predominantly from low opex variable renewables with a tiny sliver of high opex dispatchable backup plant at the margins.

Thanks for reading Energy Flux! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Structural reliance

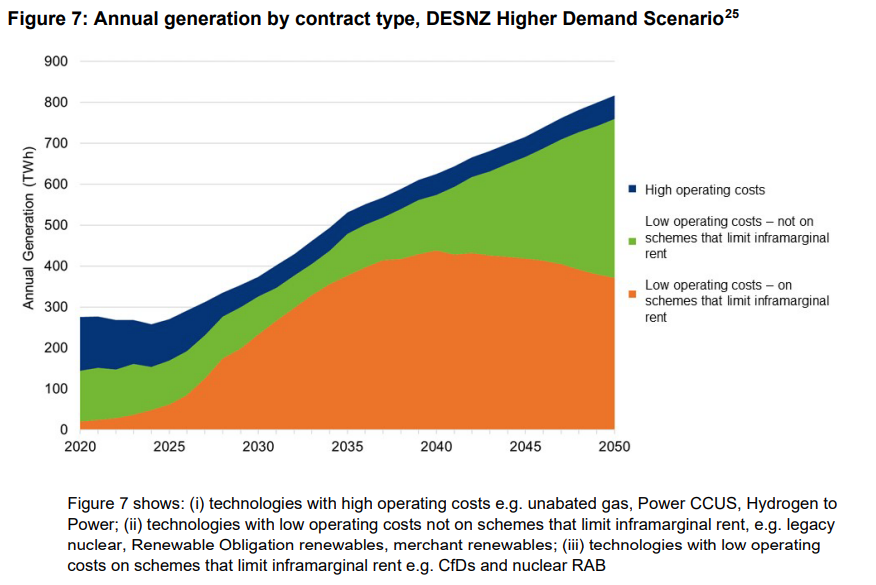

And even when we get there, the new system could be as volatile as the old one. DESNZ modelling indicates there could be an ongoing structural reliance on low-carbon high opex marginal generation sources (such as gas with carbon capture) beyond 2050.

Furthermore, from 2035 onwards renewable generation is expected to shift away from CfD-type regimes that protect consumers towards merchant trading arrangements that do not limit inframarginal rent. The scope for political intervention to claw back extraordinary inframarginal profits will not diminish in such a system.

Quite how volatile the transition and destination will be depends a lot on the policy decisions yet to be made by DESNZ.

The government’s response to the second REMA consultation was expected in “summer 2024”. Whenever it arrives, locational pricing may or may not be part of the mix. But marginal pricing – for better or worse – definitely will be.

- This article was first published in E-FWD — read the original. Reproduced here with permission.

More from Energy Flux:

Member discussion: Madness at the margins

Read what members are saying. Subscribe to join the conversation.